|

Defoliation was meant to save lives by denying the enemy cover. But for some the 'cure'

was worse than the problem.

By Tony Spletstoser

The primary use of herbicides in Vietnam was to kill vegetation

and thereby deny cover to enemy forces. Heavily sprayed areas included

inland forests near the Demilitarized Zone and along the South Vietnamese

borders with Cambodia and Laos, and the mangrove forests in the Rung Sat

Special Zone along the river approaches to Saigon and in the Mekong Delta's

Ca Mau Peninsula.

The process was called defoliation, and it is nothing new. The American

agriculture industry has long been using chemicals to make the leaves fall

off cotton and soybean plants just before the mechanized picking machines

go into the fields. The chemical 2,4-D and its variants had been applied

to U.S. acreage by either crop duster-sprayer aircraft or ground spray

machines for years. But since the early '60s, the law has required

applicators, sprayer pilots and ground personnel to study and pass tests

before being allowed to handle or apply defoliants. They wear special

coverall flight suits, boots, face masks and gloves when handling the

chemicals, and are warned that the defoliant is a poison.

Such precautions, however, were not taken in South Vietnam between 1965

and 1971. Defoliants were handled carelessly and applied carelessly,

sprayed on both the enemy and noncombatants, and even our own men. To

compound the problem, our armed forces were told that the chemicals were

harmless to humans, despite early evidence to the contrary.

The 55-gallon drums of herbicide were identified by 4-inch-wide circular

bands of orange paint. Agent Orange (named for the chemical containers'

color banding) in theory was harmless to humans, and its persistence in

the soil was limited to only a few weeks. It was maintained that very high

dosages were necessary to produce any adverse effects on humans. However,

some Americans voiced considerable concern over the potential danger from

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-paradioxin, commonly known as Dioxin, an

impurity present in 2,4,5-T, the latter being the chemical compound Agent

Orange. Some 11,712,860 gallons of Agent Orange were sprayed on South

Vietnam between 1965 and 1971, and the defoliant was later alleged to have

caused long-lasting health problems.

Agent Blue, 100 percent sodium salt of cacodylic acid, is an arsenic

compound that was also sprayed over Vietnam. Although the organic compound

is not as toxic as the inorganic forms of arsenic, such as sodium arsenite,

it can be fatal to both animals and humans. A probable lethal oral dose

would be one ounce or more. There is no accurate way of gauging the effect

of the 2,161,169 gallons of Agent Blue sprayed on South Vietnam between

1965 and 1971 on drinking water and food stuffs used by the indigenous

people.

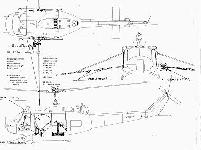

Air Force Fairchild UC-123 Providers rigged as spray planes applied most

of the defoliants in Vietnam. They had the A/A45Y-1 herbicide spraying

system installed, with 1,000-gallon pressure pumping tanks in the cargo

compartment. The spray material was routed to spray booms mounted on

hangers attached just forward of the aileron cutouts on each wing. The

Providers usually flew in a five-plane formation with fighter-bomber top

cover as well as helicopter gunships for close air support.

The defoliation program called Operation Ranch Hand lasted from January

1965 until February 1971. Ranch Hand aircraft were based at Tan Son Nhut,

Bien Hoa, Phan Rang, Nha Trang and Da Nang. There were occasions when,

pressed for time, aircraft were flown not rigged as spray planes but with

the forward side doors open and the rear ramp lowered. The flight crew

handlers simply took fire axes, chopped holes in the 55-gallon drums,

dumped them over on the deck near the rear ramp and let the vortexes suck

the material out of the aircraft, creating its own spray. These same

vortexes swirled the spray back inside the aircraft, completely soaking

the air crew. Even when the crews used spray equipment, it was impossible

not to be covered with the herbicide.

The lives of those UC-123 crewmen were in jeopardy at all times. In order

for the defoliant spray to be effective, the aircraft had to be flown low,

in a consistent flight track, and at airspeeds not much higher than 85

knots. This made for really good ground-fire target practice by the enemy.

After April 1969, all Ranch Hand operations used the jet-equipped UC-123K.

Some experimental high-speed runs were made at airspeeds of 180 knots, but

overall the high-speed approach did not work out. Normal spraying speed

was 130 knots at the lowest possible altitudes.

Those low flights could be dangerous business. On the morning of

April 7, 1969, for example, a formation of seven Ranch Hand aircraft had

planned to make three separate passes over their targets in the U Minh

forest. On the first pass, all but one were hit by machine-gun fire.

Two of the UC-123Ks each lost an engine and immediately headed to Bien Hoa.

The five remaining aircraft received ground fire on the second pass, the

last plane in the formation losing effective aileron control as bullets

penetrated its left wing and control surfaces. Other bullets struck the

leading edge of the right wing near the wing root. There, fuel and

electrical lines were cut, and a fire started that was fed by the booster

pump. The crew was forced to make an emergency landing at Ben Tre, and the

aircraft was damaged beyond repair.

While the UC-123 pilots were fairly well protected from the chemical by

their position up on the flight deck, the other crew members who had to

handle the spray equipment had no way to avoid exposure to Agent Orange.

No protective clothing or even special handling orders were issued.

U.S.Army helicopters were also used to apply Agent Orange, and "Lucky" piloted

one of those choppers. In December 1970, "Lucky" was assigned to the 114th

Assault Helicopter Company at Vinh Long in the Mekong Delta.

At first, Lucky flew conventional troop lift insertions; then one day he

was selected for a different assignment, spraying defoliant.

U.S.Army helicopters were also used to apply Agent Orange, and "Lucky" piloted

one of those choppers. In December 1970, "Lucky" was assigned to the 114th

Assault Helicopter Company at Vinh Long in the Mekong Delta.

At first, Lucky flew conventional troop lift insertions; then one day he

was selected for a different assignment, spraying defoliant.

An Army team out of Saigon came in with the engineering and equipment to

convert Bell UH-1H Huey helicopters into sprayers for the Agent Orange

chemical.

By this time in 1971, the Ranch Hand operation had been pretty much shut down, but there still were

plenty of 55-gallon drums of Agent Orange around. Lucky's mission was to spray a site in the U Minh Forest.

As opposed to the five to seven UC-123Ks on spray flights, his flight consisted of only his one spray-rigged

helicopter, a command-and-control ship, and two Bell AG-1 Cobra gunships.

Lucky and his crew flew south to a landing zone located on the edge of the forest to load up with Agent

Orange. The spray rig in the helicopter consisted of the deck-mounted tank fixture supporting the spray

booms that extended out on each side to about three-quarters of the rotor-blade span. The spray tank of

approximately 200 gallons took up the entire cargo compartment between the back of the pilots' seats and

the transmission compartment bulkhead. The spray booms were served by a wind-driven pump that had a

24-inch-diameter, four-bladed propeller. Lucky's two enlisted crewmen had the job of manning the door

guns while in the air and refilling the tank when it was empty. The drill was to fly low over the trees

at 75 to 80 knots, which was about as fast as they could go.

The Huey managed to stay ahead of the spray mist except on the turns at the end of each pass or when the

wind changed direction. There was always a certain amount of spray mist drifting through the aircraft.

Before the day was done, all of the air crewmen were pretty well soaked. When the tank was empty, Lucky

would return to the landing zone, where the ground crew manhandled the 55-gallon drums over to the aircraft,

and his crew hand-pumped the defoliant material into the big tank on board. It took longer to refill than it

did to spray it out.

Lucky's part of this mission lasted two days. Now, some 25 years later, he isn't exactly sure how many

refills he flew a day, but he believes that he flew four sorties daily, which meant that he probably put out

a total of about 1,600 gallons of herbicide. After that, another air crew from the 114th took over. He never

had occasion to return to that area, but other pilots told him that after three or four weeks the sprayed

area started greening up as the plants put out new leaves. Everything was growing again.

At the time, Lucky had no idea of the catastrophe that flying the sprayer helicopter would make of his life.

A few years after he returned home, the psychological, emotional and physical problems caused by Agent Orange

began to surface. It took a while for Lucky to connect his problems with his two days of forest spraying. It

took even longer to get any satisfaction out of the Veterans Administration (VA). No one wanted to admit that

Agent Orange would cause any health problems. In 1976, Lucky had a vasectomy after learning that a friend who

had served with the 101st Airborne had had two children born with severe birth defects after his stint in

Vietnam.

After thousands of sheets of paperwork and medical tests, Lucky finally received a

100-percent service-connected medical disability. The VA, however, continued to insist that his disability

had nothing to do with Agent Orange.

In 1990 Lucky remarried, and his new wife has indicated that she would like to have children. On one of his

check-up visits to the VA hospital, he asked his doctor if it was possible to reverse a vasectomy. The VA

doctor told Lucky that there would be a 50-50 chance of success, but that he would advise against it because

of Lucky's exposure to Agent Orange.

|